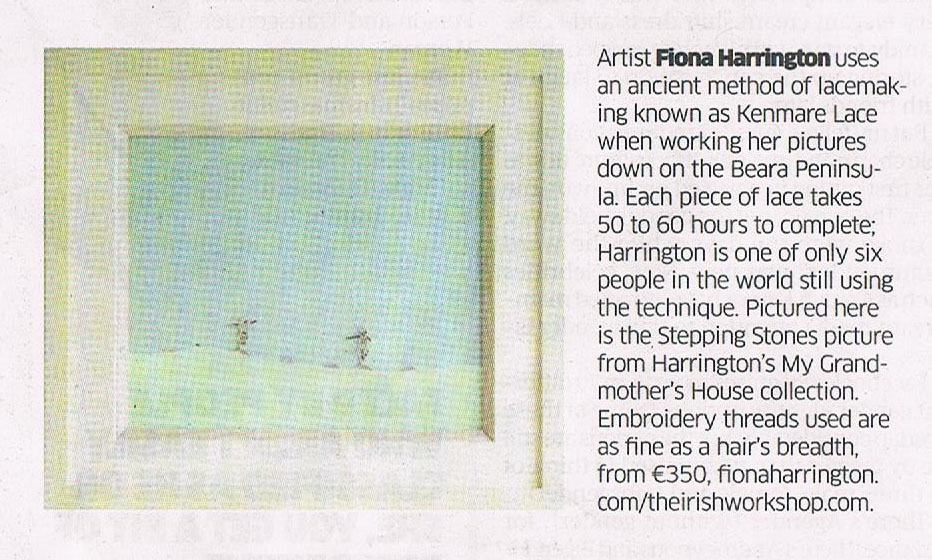

Irish Examiner, August 20th 2014

/in Press /by Fiona HarringtonSmall wonders put new twist on old tradition

Today we are so technologically-minded we can hardly remember a world where everything was not accessible at the click of a mouse, where a desired item was not instantly purchasable online, but took days,weeks, months to create.

Yet scarcely two or three generations back, it was the way we all lived. If you wanted something — be it a field cleared or a coat mended — you did it yourself. If you were an artist, a craftworker, you spent long hours at your easel or workbench, creating something of beauty. Ireland was renowned for its exquisite crafts, and many a household relied on the income brought in by the making of lace. Among the treasures lost on that last ill-fated voyage of the Titanic were handmade Irish lace blouses, purchased in Cobh on the ship’s final call. They would be priceless today.

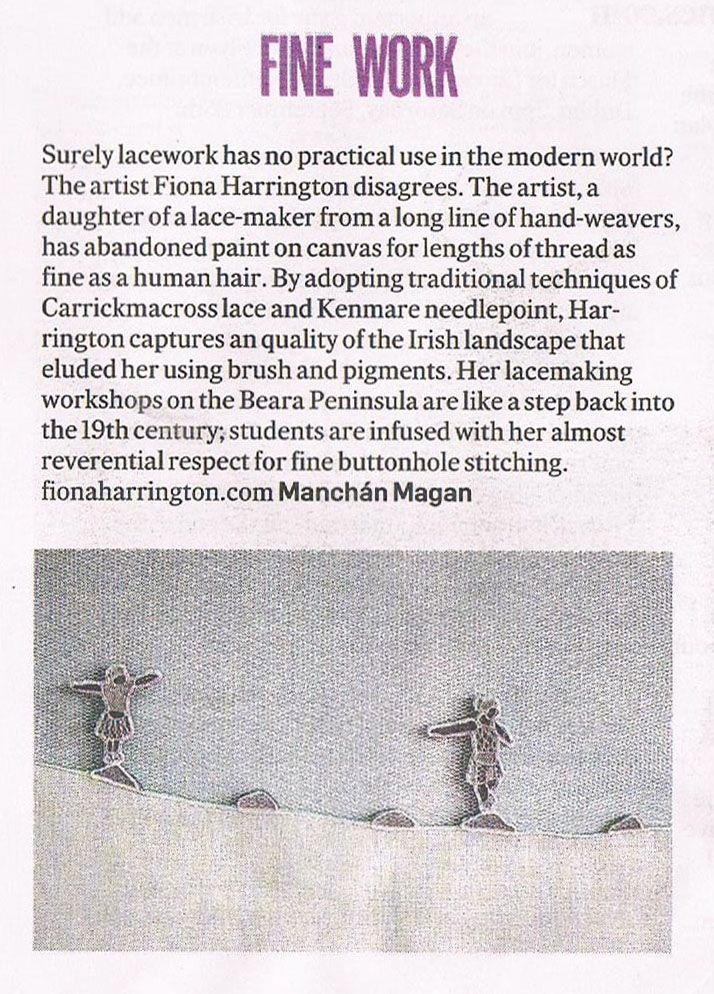

In an age, though, when we can see comparatively inexpensive machine-made versions in any huge department store, should the painstaking and time-consuming traditional craft of handmade Irish lace be forgotten, or at least consigned to the realm of gentle hobbywork? One doughty Irish artist doesn’t think so. Recently, Beara-based artist Fiona Harrington has been making considerable waves in the age-old world of lacemaking, showing how an old craft can be combined with new ideas, creating stunningly different visual pieces.

Ms Harrington, who graduated in fine art painting from the Crawford in Cork in 2001, spent a decade living and painting both in Beara and in New Zealand. Her work was exhibited extensively, and purchased by many private collectors as well as by public bodies.

Nevertheless, lacework was in her blood. “My mother was a lacemaker and she came from a long line of hand weavers and needle workers. That surely affected my choice when I went to the National College of Art and Design in Dublin.” Finding that the course she intended to take was full, she opted for textile design instead. And that, says Harrington, changed her entire outlook. “I chose the history of Irish lace, completing my studies at the Kenmare Lace and Design Centre. When I graduated in 2013, I was the only person in the country to specialise in handmade Irish lace.”

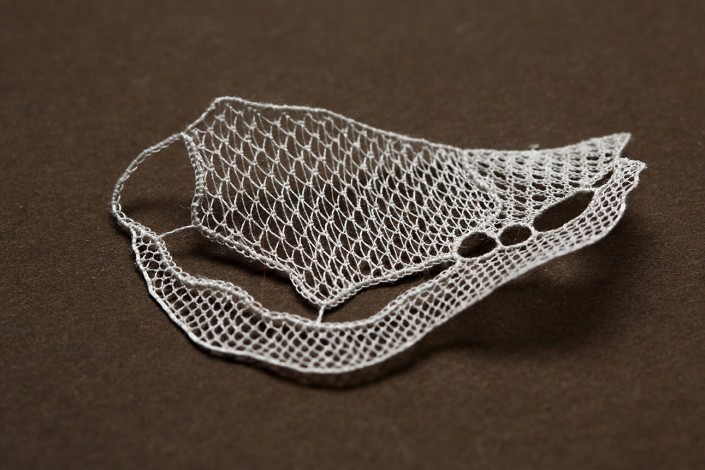

Her creative instinct saw how both her skills could be combined to create something entirely new. And it worked. In 2013 she won the prestigious RDS Graduate Prize and this year, first prize in the lace category and the Eleanor De La Branchardiere award for innovative lace design, both at the National Craft Awards in Dublin. This was for a unique miniature piece which encapsulated the rugged West Cork coastline in a myriad different lace patterns. “It was what I always saw from my window, the different textures in the fields, the hedges, the cliffs, and I worked out how to recapture that in the stitchery.” The finely-worked piece, tiny yet so detailed, is a truly amazing work of art.

The little pictures hanging on the wall in her studio almost leap off into your hands, begging to be taken home. A tiny lost lamb, a magical miniature Irish oak tree, a splendid fox — all set in misty backgrounds which demonstrate clearly the artist’s grasp of presentation.

“I don’t want our proud tradition to be forgotten. I see this as a way to develop it, to carry it on,” says Harrington.

-[url=www.fionaharrington.com/]. Her new collections can be seen at The Sarah Walker Gallery in Castletownbere, Co Cork, and Cleo in Kenmare, Co Kerry.

© Irish Examiner Ltd. All rights reserved

Press

/in Uncategorised /by Fiona HarringtonSmall wonders put new twist on old tradition

Today we are so technologically-minded we can hardly remember a world where everything was not accessible at the click of a mouse, where a desired item was not instantly purchasable online, but took days,weeks, months to create.

Yet scarcely two or three generations back, it was the way we all lived. If you wanted something — be it a field cleared or a coat mended — you did it yourself. If you were an artist, a craftworker, you spent long hours at your easel or workbench, creating something of beauty. Ireland was renowned for its exquisite crafts, and many a household relied on the income brought in by the making of lace. Among the treasures lost on that last ill-fated voyage of the Titanic were handmade Irish lace blouses, purchased in Cobh on the ship’s final call. They would be priceless today.

In an age, though, when we can see comparatively inexpensive machine-made versions in any huge department store, should the painstaking and time-consuming traditional craft of handmade Irish lace be forgotten, or at least consigned to the realm of gentle hobbywork? One doughty Irish artist doesn’t think so. Recently, Beara-based artist Fiona Harrington has been making considerable waves in the age-old world of lacemaking, showing how an old craft can be combined with new ideas, creating stunningly different visual pieces.

Ms Harrington, who graduated in fine art painting from the Crawford in Cork in 2001, spent a decade living and painting both in Beara and in New Zealand. Her work was exhibited extensively, and purchased by many private collectors as well as by public bodies.

Nevertheless, lacework was in her blood. “My mother was a lacemaker and she came from a long line of hand weavers and needle workers. That surely affected my choice when I went to the National College of Art and Design in Dublin.” Finding that the course she intended to take was full, she opted for textile design instead. And that, says Harrington, changed her entire outlook. “I chose the history of Irish lace, completing my studies at the Kenmare Lace and Design Centre. When I graduated in 2013, I was the only person in the country to specialise in handmade Irish lace.”

Her creative instinct saw how both her skills could be combined to create something entirely new. And it worked. In 2013 she won the prestigious RDS Graduate Prize and this year, first prize in the lace category and the Eleanor De La Branchardiere award for innovative lace design, both at the National Craft Awards in Dublin. This was for a unique miniature piece which encapsulated the rugged West Cork coastline in a myriad different lace patterns. “It was what I always saw from my window, the different textures in the fields, the hedges, the cliffs, and I worked out how to recapture that in the stitchery.” The finely-worked piece, tiny yet so detailed, is a truly amazing work of art.

The little pictures hanging on the wall in her studio almost leap off into your hands, begging to be taken home. A tiny lost lamb, a magical miniature Irish oak tree, a splendid fox — all set in misty backgrounds which demonstrate clearly the artist’s grasp of presentation.

“I don’t want our proud tradition to be forgotten. I see this as a way to develop it, to carry it on,” says Harrington.

-[url=www.fionaharrington.com/]. Her new collections can be seen at The Sarah Walker Gallery in Castletownbere, Co Cork, and Cleo in Kenmare, Co Kerry.

© Irish Examiner Ltd. All rights reserved

West Cork Times August 07, 2014

/in Press /by mvealeWEST CORK LACE DESIGNER WINS RDS CRAFT AWARDS COMPETITION

by Stephen Johnson

EYERIES lace designer and artist Fiona Harrington has won the Lace Category Prize — the Eleanor De La Branchardière Award worth €1,200 — for her piece “Deserted Cottage” at the Royal Dublin Show National Crafts Awards Competition.

EYERIES lace designer and artist Fiona Harrington has won the Lace Category Prize — the Eleanor De La Branchardière Award worth €1,200 — for her piece “Deserted Cottage” at the Royal Dublin Show National Crafts Awards Competition.

Fiona’s work combines Carrickmacross and Kenmare needlepoint lace techniques, using both traditional and unconventional approaches to lace.

Fiona studied lacemaking at the Kenmare Lace Centre, where a strong tradition of lacemaking exists. It was introduced to the Town in 1861 by the Poor Clare nuns as a mean of creating employment and industryafter the Great Famine.

Dating back almost 200 years, Carrickmacross is the oldest of Irish laces. Using sapplique and cut-away techniques, this style of lace is native to Co. Monaghan.

Recognised as a “pure lace”, Kenmare needlepoint is produced using only a needle and thread — thread as fine as a human hair.

The two techniques are intricate and highly complex, requiring hours of focused concentration.

Fiona’s studio overlooks the Atlantic Ocean on the Beara Peninsula between the village of Eyeries and Castletownbere.

In an interview at her studio with the West Cork Times, Fiona said that her work is inspired by the landscape of West Cork. “As a child, I spent much of my time in West Cork, roaming through fields and exploring the wonders of the countryside.”

Source: West Cork times

My Lace Story

/in Events, Lace /by mveale In 2012 I was in the third year of an undergraduate degree at the National College of Art and Design in Dublin. I was studying textile design and had chosen a ‘Contemporary Themes in Craft’ module for visual culture. This was the theory based part of my degree. During one session, my lecturer Anna Moran had spoken about an exhibition which was taking place in Birmingham called Lost in Lace, curated by Lesley Millar, professor of Textiles at the University of Creative Arts. She showed us some slides and spoke about how this exhibition dealt with the idea of traditional making but in a modern way and she urged us to go and see the show. It didn’t seem to have that much impact on my classmates but I was enthralled. I booked my flight to Birmingham!

In 2012 I was in the third year of an undergraduate degree at the National College of Art and Design in Dublin. I was studying textile design and had chosen a ‘Contemporary Themes in Craft’ module for visual culture. This was the theory based part of my degree. During one session, my lecturer Anna Moran had spoken about an exhibition which was taking place in Birmingham called Lost in Lace, curated by Lesley Millar, professor of Textiles at the University of Creative Arts. She showed us some slides and spoke about how this exhibition dealt with the idea of traditional making but in a modern way and she urged us to go and see the show. It didn’t seem to have that much impact on my classmates but I was enthralled. I booked my flight to Birmingham!

When I arrived at the Gas Hall, I was amazed. The architecture of the building itself was so impressive. I spent the day wandering around the exhibition. I was awestruck. Every piece of artwork excited me- the sheer scale of the work, the delicacy and the fact that I could see through most of the materials.

I had always been fascinated by holes. When I painted I was always inspired by voids and crevasses and the idea of something within the nothing. I have often thought about where this interest came from, I was never really sure but I do know that one of my heroes Georgia O Keeffee had a similar fascination. Perhaps this is where it started?

When I returned from Birmingham I knew that this was what I wanted to do. I wanted to make work like this- large scale, delicate and see through. I thought this whole lace thing must be fascinating if so many people can make such different work and yet still be connected in some way. I also however felt that if I was going to make work which reflected lace then firstly I should really learn about the structure and the process of lacemaking.

I had always known that lacemakers existed in Ireland. My mother made lace when I was young before she got sick and I have many memories of her sitting with a needle and thread or her cushion and collection of bobbins. I was young then and had no interest in these things and sadly by the time I did develop an interest in lace, my mother had died. I was very lucky though to have found her lace box containing all her lacemaking tools and threads as well as some of her actual lace. These are now of course invaluable to me!

During my research I discovered that a lace making centre existed in Kenmare- a small town in Southwest Ireland, just a stone’s throw from my Nana’s house. I was so excited. I contacted Nora Finnegan- the director of the centre and asked if she would be interested in teaching me lace. She agreed and In June 2012 I began my training. I spent 4 months here learning traditional Kenmare Lace- a needlepoint technique made entirely form a tiny needle and a thread as fine as a human hair. I also learned Carrickmacross and Bobbin Lace as well as the history of all the Irish laces.

When I returned to college in October to finish my degree I was completely hooked. This of course posed a bit of a problem. I was basically practicing a 150 year old technique. I had learned in the traditional way, following the patterns that had been drawn up by the Poor Clare nuns in the mid 19th century. This would never work at the National College of Art and Design. Here, students were encouraged to be innovative and emphasis was not placed on tradition. Also, lace was not taught at NCAD and nobody there could offer me guidance or instruction on technique.

I continued to practice however and also began to make my own patterns. This was difficult. I50 year old patterns are tried and tested, mine were not. You begin to realise fairly quickly why processes are repeated, because they work! Any time I tried to make a shortcut or any time I thought I was being clever; it became apparent I was not. The reality is with lace, you have to follow the process, it takes time and you must be willing to dedicate yourself to that time.

Through a lot of perseverance, practice and focus however I did manage to develop a process which allowed me to be a little bit more creative. I finally figured out how to turn my own drawings into workable lace patterns and as a result my entire degree show centred on Handmade Lace and the development of my own individual lace making process. And so began this new phase in my artistic career!

Scéal Na Cúlóige

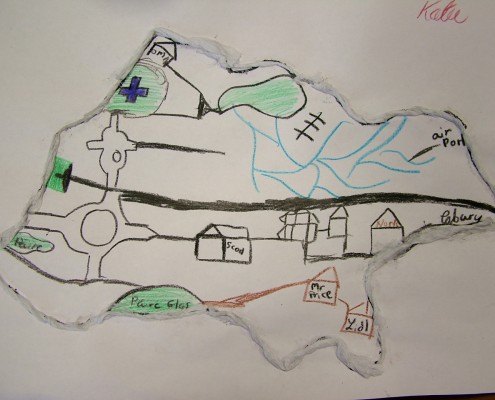

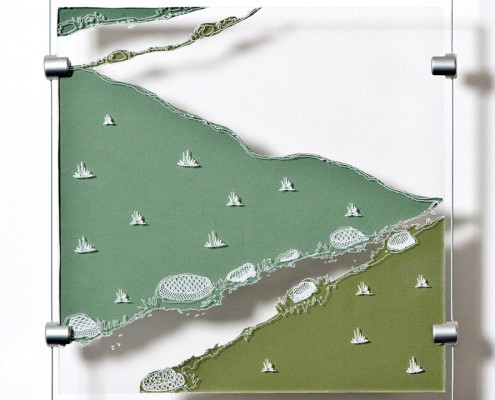

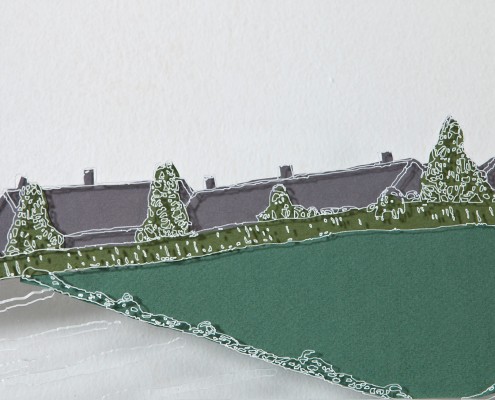

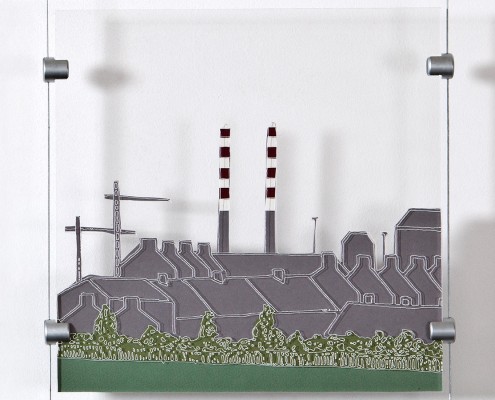

/in Lace, Projects /by mvealeIn February 2014 I came across a call to tender for a public art commission for Gaelscoil Cholmcille in Dublin. Located in Coolock, this is a primary school with about 240 children and everything in the school is taught through Irish.

I was immediately drawn to this. Firstly, the commissioners welcomed proposal from artists for either an outdoor or indoor artwork. Quite often, public art commissions are looking for outdoor works which generally disqualifies me due to the nature of the work I make. Secondly, this was a Gaelscoil and I always loved Irish. I was constantly looking for opportunities to practice and improve mo theanga.

The school and the selection panel were very open to artists’ suggestions but there were a few requirements. They wanted the artwork to reflect the school’s ethos Moladh agus Mealladh (praise and encouragement) and also to involve and engage the children of the school as much as possible. I began to research!

I have always been interested in history so I started by looking into the history of Coolock and the surrounding area. I was fascinated. The story goes back as far as the Bronze Age with a substantial amount of archaeological evidence which still exists today. There was so much to see and so much to learn. I attended Cholaiste Dhulaigh in Coolock in 1998 to complete a course in Art and Design. Little did I know that a burial tomb was discovered right next door!

I wrote a proposal, did some drawings and sent in an application. I sent in so many job applications that year I had actually lost count. So I was absolutely delighted when I received a call from the principal to let me know my proposal had been successful.

Part of my plan was to spend 6 weeks in the school running a series of textile based workshops. The workshops were based on the research which I had done of the area, but the outcome of each class depended entirely on the children’s creativity. The idea was that their artwork would inform and inspire my final designs. I taught every child in the school every week and loved every moment. Everything was through Irish. This was difficult, teaching in a language in which you are not fluent definitely adds to the workload but it was so worth it. Both the staff and the students were very patient and understanding and in fact, the children ended up teaching me quite a lot!

I documented their work on a weekly basis so when I returned to the studio to begin making the artwork I had so much inspirational material.

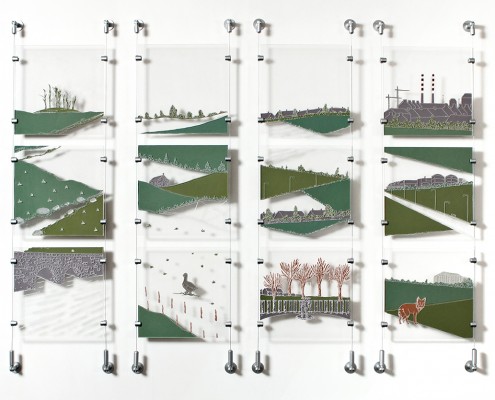

The initial proposal outlined a plan for a piece which would comprise of a series of plexiglass panels. These panels would be engraved and lasecut and contain elements of the children’s work as well as some handmade lace. I needed to find a laser cutter!

I moved into a communal arts space in Dublin where I set up my new studio. Coincidentally, a lasercutter was also working from this space. Rory Stoney had just set up Stoney CNC, so technically he was not a laser cutter but a CNC operator (computer numerical control). I approached him, told him my idea and he said he could help and so began the partnership between CNC and the arts. This was an unusual partnership. Neither of us had any idea how this would work. His machines had never cut from original hand drawn artwork, and my artwork had never been reproduced by a CNC machine! Uncommon ground!

Following a lot of toing and froing and learning each other’s ‘industry lingo’ we finally began to understand each other. Rory had only a few windows of opportunity for work so it was really important to keep on top of producing designs and drawings. This was in fact great for me as it left no time for procrastination. By the second week in January all 12 panels had been cut and engraved and all 12 backing panels were ready.

I had also started making some handmade lace. It was essential that this would be incorporated into the piece. It also became apparent that colour elements were needed as it was difficult to see the engraved lines of the drawing once the panels were hanging against the wall. I chose a palette of subtle greens and greys but still left quite a lot of open space, just as open space is so important in the process of making lace.

Everything was coming together. I found the perfect hanging system from Douglas Displays in Tallaght, adding a very slick and contemporary finish to the piece. It was expensive, but worth it!

Finally, D-Day, the official unveiling. The school went to great effort. All the children, teachers and some parents gathered in the hall. We cut the ribbon, there was music, tea and the best brownies I have ever tasted!

Boundaries

/in Lace, Projects /by mvealeProject Duration: October 2012- June 2013

Boundaries was the title given to my final year degree show. The piece was based on research I had done on a small area of farmland in southwest Cork. This land had been passed down through my father’s family for several generations.

I found the original maps which showed the historical boundaries and I also researched the first ordinance survey maps of the area which were made during the 19th century. I made a lot of drawing s but by far the most valuable information I gathered was through talking to my uncle. He had inherited the land and he told me about all the different names and words which were used to describe the specific areas of farmland. These words were never written down or recorded on any map and as a result the spelling of these land names were unclear. Without doubt, these words had derived from the Irish language but without any proper denotation, it was very difficult to work out any meaning. It was merely an oral record.

What struck me was that these words would soon be forgotten. There was no new generation of farm workers for this land and if no workers existed, there would be no need to use the words. This idea of loss fascinated me and I wanted to do something to document this unique local lingo.

I was of course at this stage making lace- another aspect of our culture which is in danger of disappearing! In a way it was fitting that I should use lace to represent this idea of loss.

I made an exhibition piece which focussed on this area of land with a series of lace samples that represented the farmland. The title of each lace piece was the name of an area of land. A map was hand drawn and hand cut and borderlines were hand painted. To convey the idea of preciousness, the work was placed in a hand-made display case, all of which was designed by me.