The origins of Irish Lace are without doubt traced to European lace samples. In the mid 19th century Italian Lace was unpicked by Irish nuns in order to work out its complex patterns. This provided the starting point and a sound framework for hundreds of women to learn about lace technique. It didn’t take long however before Irish lace makers began to experiment and explore other possibilities. The techniques were soon adapted and in no time Irish Lace, of distinctive Irish quality was being produced! In some areas up to 50 new stitches were developed! Each stitch was named and usually represented what the women saw around them such as the birds, animals or flowers. In Carrickmacross lace for example the pheasant’s eye, the crow’s foot, and the roche’s eye are just a few of the aptly named stitches.

traced to European lace samples. In the mid 19th century Italian Lace was unpicked by Irish nuns in order to work out its complex patterns. This provided the starting point and a sound framework for hundreds of women to learn about lace technique. It didn’t take long however before Irish lace makers began to experiment and explore other possibilities. The techniques were soon adapted and in no time Irish Lace, of distinctive Irish quality was being produced! In some areas up to 50 new stitches were developed! Each stitch was named and usually represented what the women saw around them such as the birds, animals or flowers. In Carrickmacross lace for example the pheasant’s eye, the crow’s foot, and the roche’s eye are just a few of the aptly named stitches.

Not only did the women focus on personalising technique, they also wanted to create designs that were meaningful and expressive. They worked hard on improving drawing skills so that they could produce patterns which could match any European lace! An art teacher was employed in Kenmare to teach drawing. Both the lace teachers and the lace makers benefitted from this sharing of skills and increased knowledge.

Ireland was known for 5 different styles of lace. They were Limerick, Carrickmacross, Irish Flat Point (or needlepoint), Clones Crochet Lace and Borris Lace. Each of these towns became centres of lace and while the town refers to the place where they originated it also distinguishes between the varieties of styles. No style however was exclusively produced in any town. In Kenmare for example, the lace makers were proficient in the production of Flat Point, Carrickmacross and Limerick. The centre that is still operational in the town today also has quite a few lace makers producing beautiful examples of Crochet Lace. So lovely to see that this tradition still continues in Kenmare!!

Carrickmacross is considered the oldest of Irish Laces. Its history dates back to the early 19th century. The original examples consisted of a layer of muslin, where the design was outlined using a thick thread. The outline was connected using ‘bars’ consisting of numerous tiny stitches and the muslin was then cut away, leaving an open-work fabric. It was not until the availability of machine made net that we start to see more decorative versions of this lace. With the arrival of this fabric, the muslin was then tacked to the netting and the design was outlined using a thick thread. The lace maker then cut away both the muslin and the net in some areas and in others, cut away only the muslin. The remaining netted area could then be embellished using a variety of carefully worked stitches. Sounds complicated? Well it is. You should try making!

Limerick Lace is arguably the less complicated style of lace. There are two varieties; Limerick Run and Limerick Tambour. The former made with a needle and thread, the latter uses a tambour hook.

Netting is supported within a frame or tambour ring. Tambour lace is made by weaving a tambour hook in and out of the netting to create a chain stitch. Limerick Run is made using a sewing needle to darn a variety of decorative stitches into the netted fabric. A skilful lace maker could produce a piece of Limerick lace in a comparatively quick amount of time! Limerick Lace was also the style mainly used for mourning lace. This lace was always made in black and it wasn’t really until later in the 20th century that black lace became fashionable. Limerick Lace boasts a huge variety of filling stitches, some samples containing up to 47 decorative stitches!!

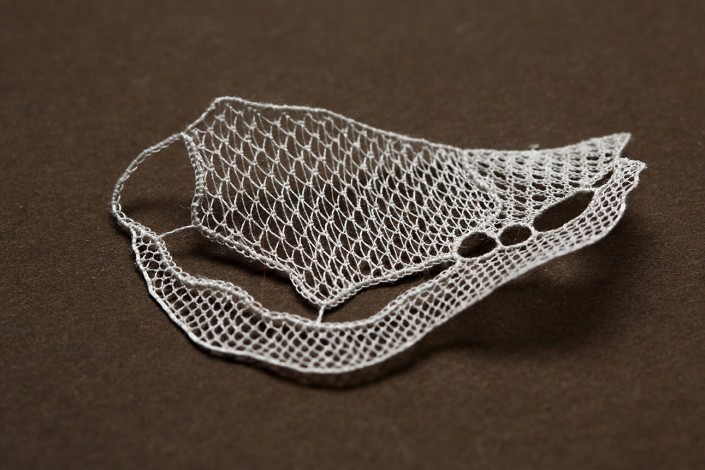

Irish Flat Point or Needlepoint was produced in a number of different centres around the country including Kenmare, Youghal, Inismacsaint and New Ross. It is made entirely from a needle and thread: the finer the thread, the finer the lace. In most cases the thread was finer than a human hair and often a magnifying glass was used to identify individual stitches. Originally a linen thread was used; however today it is difficult to get linen without lumps, so a cotton thread is used instead. To begin, 2 pieces of green cotton are tacked together (green is best as it’s easier to see the stitches) The design is placed on top and held in place using a special lace contact. The lace maker now begins to outline the pattern by couching a thread down. This thread is held in place using bridging stitches. When the outline is complete, the process of lace stitching begins. There are a number of needlepoint stitches to choose from but practically all are based on the buttonhole stitch. The variety in appearance is a result of how the stitches are applied. Following on from this, the lace must be finished by working another row of tiny stitches around the outline. In Youghal, this finishing stitch was usually a tight buttonhole, while Kenmare preferred a looser brussels point. Finally the lace can be removed from the supporting cotton fabric. This is done by gently pulling the 2 pieces of cotton apart, revealing the bridging stitches. These are cut, one by one until eventually the lace can be lifted away from the supporting fabric. This is a hugely time consuming process, but what I have learned is that no matter what, you cannot take shortcuts! Believe me, I’ve tried and it’s always been a disaster!

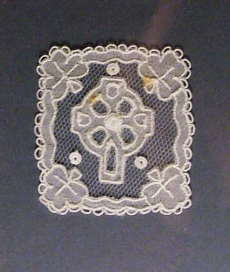

Irish Crochet laces use the same crochet technique which we are all familiar with. The difference is the crochet hook is tiny! Originally, the lace maker broke the eye of a sewing needle and this became the hook used for crochet lace. The thread used is also very fine. Firstly, a variety of motifs are made. The shamrock and rose are well known Irish designs! When the motifs are finished, they are arranged on a large supporting material, and pinned in place. From here, the lace maker begins to connect all the motifs using the chain stitch. A ‘Clones Knot’ is frequently used, similar to a picot as a way of enhancing the design.

And finally, there is Borris Lace from Co. Carlow, this is a style of tape lace. Originally the tape was handmade, however as the passementerie trade grew, ribbon and trims became more widely available. A machine made tape was then used. The pattern was first drawn onto some light coloured paper and the tape was run along the outline and held in place. The filling stitches are the same as those used in needlepoint lace. It is thought that tape lace was introduced to the town by Harriet Kavanagh following a trip to the Island of Corfu. So impressed by the Greek lace, she bought some and took it back to Ireland where she fostered the craft as a way of creating some employment for the local women.

It’s actually quite remarkable that for such a small country we managed to create such a variety of techniques, but not only this, we actually excelled in this industry. I guess in the age of globalisation, it is nice, every once in a while, to look back and remember the little things, even the tiny stitches, that set us aside from the rest of the world. Happy St Patrick’s Day Everyone.

traced to European lace samples. In the mid 19th century Italian Lace

traced to European lace samples. In the mid 19th century Italian Lace

unfortunate peasant girl, sitting by a fire, needle and thread in hand with the last light of the last candle flickering away. Indeed this was the situation for many a lace maker. However, I’m going to be quite controversial here and offer a slightly more positive twist on the Irish Lace Story.

unfortunate peasant girl, sitting by a fire, needle and thread in hand with the last light of the last candle flickering away. Indeed this was the situation for many a lace maker. However, I’m going to be quite controversial here and offer a slightly more positive twist on the Irish Lace Story. In 2012 I was in the third year of an undergraduate degree at the

In 2012 I was in the third year of an undergraduate degree at the